38 g of sardines or 2 fish oil softgels? Let us look at the numbers

The bar chart below shows the fat content of 1 sardine (38 g) canned in tomato sauce, and 2 fish oil softgels of the Nature Made brand. (The sardine is about 1/3 of the content of a typical can, and the data is from Nutritiondata.com. The two softgels are listed as the “serving size” on the Nature Made bottle.) Both the sardine and softgels have some vegetable oil added; presumably to increase their vitamin E content and form a more stable oil mix. This chart is a good reminder that looking at actual numbers can be quite instructive sometimes. Even though the chart focuses on fat content, it is worth noting that the 38 g sardine also contains 8 g of high quality protein.

If your goal with the fish oil is to “neutralize” the omega-6 fat content of your diet, which is most people’s main goal, you should consider this. A rough measure of the omega-6 neutralization “power” of a food portion is, by definition, its omega-3 minus omega-6 content. For the 1 canned sardine, this difference is 596 mg; for the 2 fish oil softgels, 440 mg. The reason is that the two softgels have more omega-6 than the sardine.

In case you are wondering, the canning process does not seem to have much of an effect on the nutrient composition of the sardine. There is some research suggesting that adding vegetable oil (e.g., soy) helps preserve the omega-3 content during the canning process. There is also research suggesting that not much is lost even without any vegetable oil being added.

Fish oil softgels, when taken in moderation (e.g., two of the type discussed in this post, per day), are probably okay as “neutralizers” of omega-6 fats in the diet, and sources of a minimum amount of omega-3 fats for those who do not like seafood. For those who can consume 1 canned sardine per day, which is only 1/3 of a typical can of sardines, the sardine is not only a more effective source of omega-3, but also a good source of protein and many other nutrients.

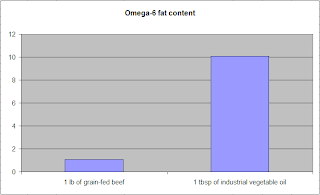

As far as balancing dietary omega-6 fats is concerned, you are much better off reducing your consumption of foods rich in omega-6 fats in the first place. Apparently nothing beats avoiding industrial seed oils in that respect. It is also advisable to eat certain types of nuts with high omega-6 content, like walnuts, in moderation.

Both omega-6 and omega-3 fats are essential; they must be part of one’s diet. The actual minimum required amounts are fairly small, probably much lower than the officially recommended amounts. Chances are they would be met by anyone on a balanced diet of whole foods. Too much of either type of fat in synthetic or industrialized form can cause problems. A couple of instructive posts on this topic are this post by Chris Masterjohn, and this one by Chris Kresser.

Even if you don’t like canned sardines, it is not much harder to gulp down 38 g of sardines than it is to gulp down 2 fish oil softgels. You can get the fish oil for $12 per bottle with 300 softgels; or 8 cents per serving. You can get a can of sardines for 50 cents; which gives 16.6 cents per serving. The sardine is twice as expensive, but carries a lot more nutritional value.

You can also buy wild caught sardines, like I do. I also eat canned sardines. Wild caught sardines cost about $2 per lb, and are among the least expensive fish variety. They are not difficult to prepare; see this post for a recipe.

I don’t know how many sardines go into the industrial process of making 2 fish oil softgels, but I suspect that it is more than one. So it is also probably more ecologically sound to eat the sardine.

If your goal with the fish oil is to “neutralize” the omega-6 fat content of your diet, which is most people’s main goal, you should consider this. A rough measure of the omega-6 neutralization “power” of a food portion is, by definition, its omega-3 minus omega-6 content. For the 1 canned sardine, this difference is 596 mg; for the 2 fish oil softgels, 440 mg. The reason is that the two softgels have more omega-6 than the sardine.

In case you are wondering, the canning process does not seem to have much of an effect on the nutrient composition of the sardine. There is some research suggesting that adding vegetable oil (e.g., soy) helps preserve the omega-3 content during the canning process. There is also research suggesting that not much is lost even without any vegetable oil being added.

Fish oil softgels, when taken in moderation (e.g., two of the type discussed in this post, per day), are probably okay as “neutralizers” of omega-6 fats in the diet, and sources of a minimum amount of omega-3 fats for those who do not like seafood. For those who can consume 1 canned sardine per day, which is only 1/3 of a typical can of sardines, the sardine is not only a more effective source of omega-3, but also a good source of protein and many other nutrients.

As far as balancing dietary omega-6 fats is concerned, you are much better off reducing your consumption of foods rich in omega-6 fats in the first place. Apparently nothing beats avoiding industrial seed oils in that respect. It is also advisable to eat certain types of nuts with high omega-6 content, like walnuts, in moderation.

Both omega-6 and omega-3 fats are essential; they must be part of one’s diet. The actual minimum required amounts are fairly small, probably much lower than the officially recommended amounts. Chances are they would be met by anyone on a balanced diet of whole foods. Too much of either type of fat in synthetic or industrialized form can cause problems. A couple of instructive posts on this topic are this post by Chris Masterjohn, and this one by Chris Kresser.

Even if you don’t like canned sardines, it is not much harder to gulp down 38 g of sardines than it is to gulp down 2 fish oil softgels. You can get the fish oil for $12 per bottle with 300 softgels; or 8 cents per serving. You can get a can of sardines for 50 cents; which gives 16.6 cents per serving. The sardine is twice as expensive, but carries a lot more nutritional value.

You can also buy wild caught sardines, like I do. I also eat canned sardines. Wild caught sardines cost about $2 per lb, and are among the least expensive fish variety. They are not difficult to prepare; see this post for a recipe.

I don’t know how many sardines go into the industrial process of making 2 fish oil softgels, but I suspect that it is more than one. So it is also probably more ecologically sound to eat the sardine.