The China Study II: Cholesterol seems to protect against cardiovascular disease

First of all, many thanks are due to Dr. Campbell and his collaborators for collecting and compiling the data used in this analysis. This data is from this site, created by those researchers to disseminate the data from a study often referred to as the “China Study II”. It has already been analyzed by other bloggers. Notable analyses have been conducted by Ricardo at Canibais e Reis, Stan at Heretic, and Denise at Raw Food SOS.

The analyses in this post differ from those other analyses in various aspects. One of them is that data for males and females were used separately for each county, instead of the totals per county. Only two data points per county were used (for males and females). This increased the sample size of the dataset without artificially reducing variance (for more details, see “Notes” at the end of the post), which is desirable since the dataset is relatively small. This also allowed for the test of commonsense assumptions (e.g., the protective effects of being female), which is always a good idea in a complex analysis because violation of commonsense assumption may suggest data collection or analysis error. On the other hand, it required the inclusion of a sex variable as a control variable in the analysis, which is no big deal.

The analysis was conducted using WarpPLS. Below is the model with the main results of the analysis. (Click on it to enlarge. Use the "CRTL" and "+" keys to zoom in, and CRTL" and "-" to zoom out.) The arrows explore associations between variables, which are shown within ovals. The meaning of each variable is the following: SexM1F2 = sex, with 1 assigned to males and 2 to females; HDLCHOL = HDL cholesterol; TOTCHOL = total cholesterol; MSCHIST = mortality from schistosomiasis infection; and MVASC = mortality from all cardiovascular diseases.

The variables to the left of MVASC are the main predictors of interest in the model – HDLCHOL and TOTCHOL. The ones to the right are control variables – SexM1F2 and MSCHIST. The path coefficients (indicated as beta coefficients) reflect the strength of the relationships. A negative beta means that the relationship is negative; i.e., an increase in a variable is associated with a decrease in the variable that it points to. The P values indicate the statistical significance of the relationship; a P lower than 0.05 generally means a significant relationship (95 percent or higher likelihood that the relationship is “real”).

In summary, this is what the model above is telling us:

- As HDL cholesterol increases, total cholesterol increases significantly (beta=0.48; P<0.01). This is to be expected, as HDL is a main component of total cholesterol, together with VLDL and LDL cholesterol.

- As total cholesterol increases, mortality from all cardiovascular diseases decreases significantly (beta=-0.25; P<0.01). This is to be expected if we assume that total cholesterol is in part an intervening variable between HDL cholesterol and mortality from all cardiovascular diseases. This assumption can be tested through a separate model (more below). Also, there is more to this story, as noted below.

- The effect of HDL cholesterol on mortality from all cardiovascular diseases is insignificant when we control for the effect of total cholesterol (beta=-0.08; P=0.26). This suggests that HDL’s protective role is subsumed by the variable total cholesterol, and also that it is possible that there is something else associated with total cholesterol that makes it protective. Otherwise the effect of total cholesterol might have been insignificant, and the effect of HDL cholesterol significant (the reverse of what we see here).

- Being female is significantly associated with a reduction in mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (beta=-0.16; P=0.01). This is to be expected. In other words, men are women with a few design flaws. (This situation reverses itself a bit after menopause.)

- Mortality from schistosomiasis infection is significantly and inversely associated with mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (beta=-0.28; P<0.01). This is probably due to those dying from schistosomiasis infection not being entered in the dataset as dying from cardiovascular diseases, and vice-versa.

Two other main components of total cholesterol, in addition to HDL cholesterol, are VLDL and LDL cholesterol. These are carried in particles, known as lipoproteins. VLDL cholesterol is usually represented as a fraction of triglycerides in cholesterol equations (e.g., the Friedewald and Iranian equations). It usually correlates inversely with HDL; that is, as HDL cholesterol increases, usually VLDL cholesterol decreases. Given this and the associations discussed above, it seems that LDL cholesterol is a good candidate for the possible “something else associated with total cholesterol that makes it protective”. But waidaminet! Is it possible that the demon particle, the LDL, serves any purpose other than giving us heart attacks?

The graph below shows the shape of the association between total cholesterol (TOTCHOL) and mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (MVASC). The values are provided in standardized format; e.g., 0 is the average, 1 is one standard deviation above the mean, and so on. The curve is the best-fitting S curve obtained by the software (an S curve is a slightly more complex curve than a U curve).

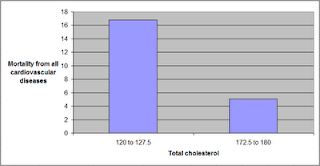

The graph below shows some of the data in unstandardized format, and organized differently. The data is grouped here in ranges of total cholesterol, which are shown on the horizontal axis. The lowest and highest ranges in the dataset are shown, to highlight the magnitude of the apparently protective effect. Here the two variables used to calculate mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (MVASC; see “Notes” at the end of this post) were added. Clearly the lowest mortality from all cardiovascular diseases is in the highest total cholesterol range, 172.5 to 180; and the highest mortality in the lowest total cholesterol range, 120 to 127.5. The difference is quite large; the mortality in the lowest range is approximately 3.3 times higher than in the highest.

The shape of the S-curve graph above suggests that there are other variables that are confounding the results a bit. Mortality from all cardiovascular diseases does seem to generally go down with increases in total cholesterol, but the smooth inflection point at the middle of the S-curve graph suggests a more complex variation pattern that may be influenced by other variables (e.g., smoking, dietary patterns, or even schistosomiasis infection; see “Notes” at the end of this post).

As mentioned before, total cholesterol is strongly influenced by HDL cholesterol, so below is the model with only HDL cholesterol (HDLCHOL) pointing at mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (MVASC), and the control variable sex (SexM1F2).

The graph above confirms the assumption that HDL’s protective role is subsumed by the variable total cholesterol. When the variable total cholesterol is removed from the model, as it was done above, the protective effect of HDL cholesterol becomes significant (beta=-0.27; P<0.01). The control variable sex (SexM1F2) was retained even in this targeted HDL effect model because of the expected confounding effect of sex; females generally tend to have higher HDL cholesterol and less cardiovascular disease than males.

Below, in the “Notes” section (after the “Reference”) are several notes, some of which are quite technical. Providing them separately hopefully has made the discussion above a bit easier to follow. The notes also point at some limitations of the analysis. This data needs to be analyzed from different angles, using multiple models, so that firmer conclusions can be reached. Still, the overall picture that seems to be emerging is at odds with previous beliefs based on the same dataset.

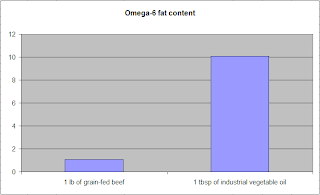

What could be increasing the apparently protective HDL and total cholesterol in this dataset? High consumption of animal foods, particularly foods rich in saturated fat and cholesterol, are strong candidates. Low consumption of vegetable oils rich in linoleic acid, and of foods rich in refined carbohydrates, are also good candidates. Maybe it is a combination of these.

We need more analyses!

Reference:

Kock, N. (2010). WarpPLS 1.0 User Manual. Laredo, Texas: ScriptWarp Systems.

Notes:

- The path coefficients (indicated as beta coefficients) reflect the strength of the relationships; they are a bit like standard univariate (or Pearson) correlation coefficients, except that they take into consideration multivariate relationships (they control for competing effects on each variable).

- The R-squared values reflect the percentage of explained variance for certain variables; the higher they are, the better the model fit with the data. In complex and multi-factorial phenomena such as health-related phenomena, many would consider an R-squared of 0.20 as acceptable. Still, such an R-squared would mean that 80 percent of the variance for a particularly variable is unexplained by the data.

- The P values have been calculated using a nonparametric technique, a form of resampling called jackknifing, which does not require the assumption that the data is normally distributed to be met. This and other related techniques also tend to yield more reliable results for small samples, and samples with outliers (as long as the outliers are “good” data, and are not the result of measurement error).

- Colinearity is an important consideration in models that analyze the effect of multiple predictors on one single variable. This is particularly true for multiple regression models, where there is a temptation of adding many predictors to the model to see which ones come out as the “winners”. This often backfires, as colinearity can severely distort the results. Some multiple regression techniques, such as automated stepwise regression with backward elimination, are particularly vulnerable to this problem. Colinearity is not the same as correlation, and thus is defined and measured differently. Two predictor variables may be significantly correlated and still have low colinearity. A reasonably reliable measure of colinearity is the variance inflation factor. Colinearity was tested in this model, and was found to be low.

- An effort was made here to avoid multiple data points per county (even though this was available for some variables), because this could artificially reduce the variance for each variable, and potentially bias the results. The reason for this is that multiple answers from a single county would normally be somewhat correlated; a higher degree of intra-county correlation than inter-county correlation. The resulting bias would be difficult to control for, via one or more control variables. With only two data points per county, one for males and the other for females, one can control for intra-country correlation by adding a “dummy” sex variable to the analysis, as a control variable. This was done here.

- Mortality from schistosomiasis infection (MSCHIST) is a variable that tends to affect the results in a way that makes it more difficult to make sense of them. Generally this is true for any infectious diseases that significantly affect a population under study. The problem with infection is that people with otherwise good health or habits may get the infection, and people with bad health and habits may not. Since cholesterol is used by the human body to fight disease, it may go up, giving the impression that it is going up for some other reason. Perhaps instead of controlling for its effect, as done here, it would have been better to remove from the analysis those counties with deaths from schistosomiasis infection. (See also this post, and this one.)

- Different parts of the data were collected at different times. It seems that the mortality data is for the period 1986-88, and the rest of the data is for 1989. This may have biased the results somewhat, even though the time lag is not that long, especially if there were changes in certain health trends from one period to the other. For example, major migrations from one county to another could have significantly affected the results.

- The following measures were used, from this online dataset like the other measures. P002 HDLCHOL, for HDLCHOL; P001 TOTCHOL, for TOTCHOL; and M021 SCHISTOc, for MSCHIST.

- SexM1F2 is a “dummy” variable that was coded with 1 assigned to males and 2 to females. As such, it essentially measures the “degree of femaleness” of the respondents. Being female is generally protective against cardiovascular disease, a situation that reverts itself a bit after menopause.

- MVASC is a composite measure of the two following variables, provided as component measures of mortality from all cardiovascular diseases: M058 ALLVASCb (ages 0-34), and M059 ALLVASCc (ages 35-69). A couple of obvious problems: (a) they does not include data on people older than 69; and (b) they seem to capture a lot of diseases, including some that do not seem like typical cardiovascular diseases. A factor analysis was conducted, and the loadings and cross-loadings suggested good validity. Composite reliability was also good. So essentially MVASC is measured here as a “latent variable” with two “indicators”. Why do this? The reason is that it reduces the biasing effects of incomplete data and measurement error (e.g., exclusion of folks older than 69). By the way, there is always some measurement error in any dataset.

- This note is related to measurement error in connection with the indicators for MVASC. There is something odd about the variables M058 ALLVASCb (ages 0-34), and M059 ALLVASCc (ages 35-69). According to the dataset, mortality from cardiovascular diseases for ages 0-34 is typically higher than for 35-69, for many counties. Given the good validity and reliability for MVASC as a latent variable, it is possible that the values for these two indicator variables were simply swapped by mistake.

The analyses in this post differ from those other analyses in various aspects. One of them is that data for males and females were used separately for each county, instead of the totals per county. Only two data points per county were used (for males and females). This increased the sample size of the dataset without artificially reducing variance (for more details, see “Notes” at the end of the post), which is desirable since the dataset is relatively small. This also allowed for the test of commonsense assumptions (e.g., the protective effects of being female), which is always a good idea in a complex analysis because violation of commonsense assumption may suggest data collection or analysis error. On the other hand, it required the inclusion of a sex variable as a control variable in the analysis, which is no big deal.

The analysis was conducted using WarpPLS. Below is the model with the main results of the analysis. (Click on it to enlarge. Use the "CRTL" and "+" keys to zoom in, and CRTL" and "-" to zoom out.) The arrows explore associations between variables, which are shown within ovals. The meaning of each variable is the following: SexM1F2 = sex, with 1 assigned to males and 2 to females; HDLCHOL = HDL cholesterol; TOTCHOL = total cholesterol; MSCHIST = mortality from schistosomiasis infection; and MVASC = mortality from all cardiovascular diseases.

The variables to the left of MVASC are the main predictors of interest in the model – HDLCHOL and TOTCHOL. The ones to the right are control variables – SexM1F2 and MSCHIST. The path coefficients (indicated as beta coefficients) reflect the strength of the relationships. A negative beta means that the relationship is negative; i.e., an increase in a variable is associated with a decrease in the variable that it points to. The P values indicate the statistical significance of the relationship; a P lower than 0.05 generally means a significant relationship (95 percent or higher likelihood that the relationship is “real”).

In summary, this is what the model above is telling us:

- As HDL cholesterol increases, total cholesterol increases significantly (beta=0.48; P<0.01). This is to be expected, as HDL is a main component of total cholesterol, together with VLDL and LDL cholesterol.

- As total cholesterol increases, mortality from all cardiovascular diseases decreases significantly (beta=-0.25; P<0.01). This is to be expected if we assume that total cholesterol is in part an intervening variable between HDL cholesterol and mortality from all cardiovascular diseases. This assumption can be tested through a separate model (more below). Also, there is more to this story, as noted below.

- The effect of HDL cholesterol on mortality from all cardiovascular diseases is insignificant when we control for the effect of total cholesterol (beta=-0.08; P=0.26). This suggests that HDL’s protective role is subsumed by the variable total cholesterol, and also that it is possible that there is something else associated with total cholesterol that makes it protective. Otherwise the effect of total cholesterol might have been insignificant, and the effect of HDL cholesterol significant (the reverse of what we see here).

- Being female is significantly associated with a reduction in mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (beta=-0.16; P=0.01). This is to be expected. In other words, men are women with a few design flaws. (This situation reverses itself a bit after menopause.)

- Mortality from schistosomiasis infection is significantly and inversely associated with mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (beta=-0.28; P<0.01). This is probably due to those dying from schistosomiasis infection not being entered in the dataset as dying from cardiovascular diseases, and vice-versa.

Two other main components of total cholesterol, in addition to HDL cholesterol, are VLDL and LDL cholesterol. These are carried in particles, known as lipoproteins. VLDL cholesterol is usually represented as a fraction of triglycerides in cholesterol equations (e.g., the Friedewald and Iranian equations). It usually correlates inversely with HDL; that is, as HDL cholesterol increases, usually VLDL cholesterol decreases. Given this and the associations discussed above, it seems that LDL cholesterol is a good candidate for the possible “something else associated with total cholesterol that makes it protective”. But waidaminet! Is it possible that the demon particle, the LDL, serves any purpose other than giving us heart attacks?

The graph below shows the shape of the association between total cholesterol (TOTCHOL) and mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (MVASC). The values are provided in standardized format; e.g., 0 is the average, 1 is one standard deviation above the mean, and so on. The curve is the best-fitting S curve obtained by the software (an S curve is a slightly more complex curve than a U curve).

The graph below shows some of the data in unstandardized format, and organized differently. The data is grouped here in ranges of total cholesterol, which are shown on the horizontal axis. The lowest and highest ranges in the dataset are shown, to highlight the magnitude of the apparently protective effect. Here the two variables used to calculate mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (MVASC; see “Notes” at the end of this post) were added. Clearly the lowest mortality from all cardiovascular diseases is in the highest total cholesterol range, 172.5 to 180; and the highest mortality in the lowest total cholesterol range, 120 to 127.5. The difference is quite large; the mortality in the lowest range is approximately 3.3 times higher than in the highest.

The shape of the S-curve graph above suggests that there are other variables that are confounding the results a bit. Mortality from all cardiovascular diseases does seem to generally go down with increases in total cholesterol, but the smooth inflection point at the middle of the S-curve graph suggests a more complex variation pattern that may be influenced by other variables (e.g., smoking, dietary patterns, or even schistosomiasis infection; see “Notes” at the end of this post).

As mentioned before, total cholesterol is strongly influenced by HDL cholesterol, so below is the model with only HDL cholesterol (HDLCHOL) pointing at mortality from all cardiovascular diseases (MVASC), and the control variable sex (SexM1F2).

The graph above confirms the assumption that HDL’s protective role is subsumed by the variable total cholesterol. When the variable total cholesterol is removed from the model, as it was done above, the protective effect of HDL cholesterol becomes significant (beta=-0.27; P<0.01). The control variable sex (SexM1F2) was retained even in this targeted HDL effect model because of the expected confounding effect of sex; females generally tend to have higher HDL cholesterol and less cardiovascular disease than males.

Below, in the “Notes” section (after the “Reference”) are several notes, some of which are quite technical. Providing them separately hopefully has made the discussion above a bit easier to follow. The notes also point at some limitations of the analysis. This data needs to be analyzed from different angles, using multiple models, so that firmer conclusions can be reached. Still, the overall picture that seems to be emerging is at odds with previous beliefs based on the same dataset.

What could be increasing the apparently protective HDL and total cholesterol in this dataset? High consumption of animal foods, particularly foods rich in saturated fat and cholesterol, are strong candidates. Low consumption of vegetable oils rich in linoleic acid, and of foods rich in refined carbohydrates, are also good candidates. Maybe it is a combination of these.

We need more analyses!

Reference:

Kock, N. (2010). WarpPLS 1.0 User Manual. Laredo, Texas: ScriptWarp Systems.

Notes:

- The path coefficients (indicated as beta coefficients) reflect the strength of the relationships; they are a bit like standard univariate (or Pearson) correlation coefficients, except that they take into consideration multivariate relationships (they control for competing effects on each variable).

- The R-squared values reflect the percentage of explained variance for certain variables; the higher they are, the better the model fit with the data. In complex and multi-factorial phenomena such as health-related phenomena, many would consider an R-squared of 0.20 as acceptable. Still, such an R-squared would mean that 80 percent of the variance for a particularly variable is unexplained by the data.

- The P values have been calculated using a nonparametric technique, a form of resampling called jackknifing, which does not require the assumption that the data is normally distributed to be met. This and other related techniques also tend to yield more reliable results for small samples, and samples with outliers (as long as the outliers are “good” data, and are not the result of measurement error).

- Colinearity is an important consideration in models that analyze the effect of multiple predictors on one single variable. This is particularly true for multiple regression models, where there is a temptation of adding many predictors to the model to see which ones come out as the “winners”. This often backfires, as colinearity can severely distort the results. Some multiple regression techniques, such as automated stepwise regression with backward elimination, are particularly vulnerable to this problem. Colinearity is not the same as correlation, and thus is defined and measured differently. Two predictor variables may be significantly correlated and still have low colinearity. A reasonably reliable measure of colinearity is the variance inflation factor. Colinearity was tested in this model, and was found to be low.

- An effort was made here to avoid multiple data points per county (even though this was available for some variables), because this could artificially reduce the variance for each variable, and potentially bias the results. The reason for this is that multiple answers from a single county would normally be somewhat correlated; a higher degree of intra-county correlation than inter-county correlation. The resulting bias would be difficult to control for, via one or more control variables. With only two data points per county, one for males and the other for females, one can control for intra-country correlation by adding a “dummy” sex variable to the analysis, as a control variable. This was done here.

- Mortality from schistosomiasis infection (MSCHIST) is a variable that tends to affect the results in a way that makes it more difficult to make sense of them. Generally this is true for any infectious diseases that significantly affect a population under study. The problem with infection is that people with otherwise good health or habits may get the infection, and people with bad health and habits may not. Since cholesterol is used by the human body to fight disease, it may go up, giving the impression that it is going up for some other reason. Perhaps instead of controlling for its effect, as done here, it would have been better to remove from the analysis those counties with deaths from schistosomiasis infection. (See also this post, and this one.)

- Different parts of the data were collected at different times. It seems that the mortality data is for the period 1986-88, and the rest of the data is for 1989. This may have biased the results somewhat, even though the time lag is not that long, especially if there were changes in certain health trends from one period to the other. For example, major migrations from one county to another could have significantly affected the results.

- The following measures were used, from this online dataset like the other measures. P002 HDLCHOL, for HDLCHOL; P001 TOTCHOL, for TOTCHOL; and M021 SCHISTOc, for MSCHIST.

- SexM1F2 is a “dummy” variable that was coded with 1 assigned to males and 2 to females. As such, it essentially measures the “degree of femaleness” of the respondents. Being female is generally protective against cardiovascular disease, a situation that reverts itself a bit after menopause.

- MVASC is a composite measure of the two following variables, provided as component measures of mortality from all cardiovascular diseases: M058 ALLVASCb (ages 0-34), and M059 ALLVASCc (ages 35-69). A couple of obvious problems: (a) they does not include data on people older than 69; and (b) they seem to capture a lot of diseases, including some that do not seem like typical cardiovascular diseases. A factor analysis was conducted, and the loadings and cross-loadings suggested good validity. Composite reliability was also good. So essentially MVASC is measured here as a “latent variable” with two “indicators”. Why do this? The reason is that it reduces the biasing effects of incomplete data and measurement error (e.g., exclusion of folks older than 69). By the way, there is always some measurement error in any dataset.

- This note is related to measurement error in connection with the indicators for MVASC. There is something odd about the variables M058 ALLVASCb (ages 0-34), and M059 ALLVASCc (ages 35-69). According to the dataset, mortality from cardiovascular diseases for ages 0-34 is typically higher than for 35-69, for many counties. Given the good validity and reliability for MVASC as a latent variable, it is possible that the values for these two indicator variables were simply swapped by mistake.