Looking for a good orthodontist? My recommendation is Dr. Meat

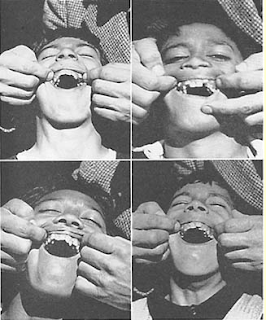

The figure below is one of many in Weston Price’s outstanding book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration showing evidence of teeth crowding among children whose parents moved from a traditional diet of minimally processed foods to a Westernized diet.

Tooth crowding and other forms of malocclusion are widespread and on the rise in populations that have adopted Westernized diets (most of us). Some blame it on dental caries, particularly in early childhood; dental caries are also a hallmark of Westernized diets. Varrela (2007), however, in a study of Finnish skulls from the 15th and 16th centuries found evidence of dental caries, but not of malocclusion, which Varrela reported as fairly high in modern Finns.

Why does malocclusion occur at all in the context of Westernized diets? Lombardi (1982) put forth an evolutionary hypothesis:

So what is one to do? Apparently getting babies to eat meat is not a bad idea. They may well just chew on it for a while and spit it out. The likelihood of meat inducing dental caries is very low, as most low carbers can attest. (In fact, low carbers who eat mostly meat often see dental caries heal.)

Concerned about the baby choking on meat? At the time of this writing a Google search yielded this: No results found for “baby choked on meat”. Conversely, Google returned 219 hits for “baby choked on milk”.

What if you have a child with crowded teeth as a preteen or teen? Too late? Should you get him or her to use “cute” braces? Our daughter had crowded teeth a few years ago, as a preteen. It overlapped with the period of my transformation, which meant that she started having a lot more natural foods to eat. There were more of those around, some of which require serious chewing, and less industrialized soft foods. Those natural foods included hard-to-chew beef cuts, served multiple times a week.

We noticed improvement right away, and in a few years the crowding disappeared. Now she has the kind of smile that could land her a job as a toothpaste model:

The key seems to be to start early, in developmental years. If you are an adult with crowded teeth, malocclusion may not be solved by either tough foods or braces. With braces, you may even end up with other problems (see this).

Tooth crowding and other forms of malocclusion are widespread and on the rise in populations that have adopted Westernized diets (most of us). Some blame it on dental caries, particularly in early childhood; dental caries are also a hallmark of Westernized diets. Varrela (2007), however, in a study of Finnish skulls from the 15th and 16th centuries found evidence of dental caries, but not of malocclusion, which Varrela reported as fairly high in modern Finns.

Why does malocclusion occur at all in the context of Westernized diets? Lombardi (1982) put forth an evolutionary hypothesis:

“In modern man there is little attrition of the teeth because of a soft, processed diet; this can result in dental crowding and impaction of the third molars. It is postulated that the tooth-jaw size discrepancy apparent in modern man as dental crowding is, in primitive man, a crucial biologic adaptation imposed by the selection pressures of a demanding diet that maintains sufficient chewing surface area for long-term survival. Selection pressures for teeth large enough to withstand a rigorous diet have been relaxed only recently in advanced populations, and the slow pace of evolutionary change has not yet brought the teeth and jaws into harmonious relationship.”

So what is one to do? Apparently getting babies to eat meat is not a bad idea. They may well just chew on it for a while and spit it out. The likelihood of meat inducing dental caries is very low, as most low carbers can attest. (In fact, low carbers who eat mostly meat often see dental caries heal.)

Concerned about the baby choking on meat? At the time of this writing a Google search yielded this: No results found for “baby choked on meat”. Conversely, Google returned 219 hits for “baby choked on milk”.

What if you have a child with crowded teeth as a preteen or teen? Too late? Should you get him or her to use “cute” braces? Our daughter had crowded teeth a few years ago, as a preteen. It overlapped with the period of my transformation, which meant that she started having a lot more natural foods to eat. There were more of those around, some of which require serious chewing, and less industrialized soft foods. Those natural foods included hard-to-chew beef cuts, served multiple times a week.

We noticed improvement right away, and in a few years the crowding disappeared. Now she has the kind of smile that could land her a job as a toothpaste model:

The key seems to be to start early, in developmental years. If you are an adult with crowded teeth, malocclusion may not be solved by either tough foods or braces. With braces, you may even end up with other problems (see this).